Overview

The New York Journal-American, the Hearst Corporation's chief daily newspaper for nearly thirty years until it closed down on April 24, 1966, was a leading New York City broadsheet for decades, with a heritage going back to the late nineteenth century and a broad-ranging reputation as one of the early cornerstones of American journalism.

More flamboyant and controversial than most of its competitors, the Journal-American was a popular and commercial success for all but the final decade of its production. Covering both national and international news, it was always most mindful of its local beat and continuously and rigorously covered the people and events of New York City with equal thoroughness. With its roots firmly established in the "yellow journalism" long associated with its founder, William Randolph Hearst (1863-1951), the Journal-American did not shy away from controversy and its editorial and feature work proved equal to its coverage of news stories and daily events. The newspaper proved to be a vibrant combination of training ground and showplace for many important journalists, columnists, reporters and photojournalists in twentieth-century America.

From its earliest beginnings the New York Journal-American also championed the use of graphics and illustrations, and it was the most successful American newspaper of its era to combine the written word with photographic imagery. At its height, it employed a staff of some two dozen photographers working on around-the-clock rotation schedules. Many professional photojournalists learned their trade and perfected their artistry working at the Journal-American and went on to successful and award-winning careers in the profession. In addition, the newspaper subscribed to most of the major national and international photo service franchises of the day—Associated Press, Wide World, United Press International, etc.—utilizing their imagery to supplement that of their local photographers and maintaining their prints in their "morgue" as well.

Throughout the decades of its publication the New York Journal-American staff maintained a morgue of all the visual and printed materials it produced, acquired, and utilized in the course of its daily production. Assembled throughout these decades the picture morgue became an archival record of the photographic imagery generated by the photographers and picture services to produce the daily newspaper. Compiled and maintained by the picture editors and their staffs, the morgue has now become a valuable record not only of the work and artistry of the photographers who produced them but also, and perhaps more importantly, a cultural and historical record of United States and world history from the 1890s through the mid-1960s. Additional supportive and crucial contextual and cross-referential information to the photographic component of the archive is provided by a microfilm copy of the Journal-American, covering the years 1895 to 1966, as well as the original clippings morgue which has been transferred to the Briscoe Center for American History.

Organizational History

The roots of the New York Journal-American go back to William Randolph Hearst, the millionaire American publisher who founded his first newspaper, the San Francisco Examiner, in 1895. Meeting with success with this first daily broadsheet, Hearst cast his eye upon the potentially lucrative New York market and discovered the New York Morning Journal. The Journal had been founded by Hearst's former mentor, Albert Pulitzer, in 1881 and subsequently purchased by publisher John R. McLean in 1894. McLean, however, had found the New York market too difficult and sold the paper at a loss in the next year to Hearst for the sum of $180,000.

Hearst took over the paper in November of 1895, spending large amounts of money on improving its production and, most especially, purchasing talented editors and reporters—chiefly from his major competitor, Joseph Pulitzer's New York World. In the following year, he had changed the name of the paper to the New York Journal, continuing to issue it as a morning edition, and established what would become an equally successful evening edition as well. Over the course of the following half decade, both editions underwent modifications in their official names, finally becoming stable in 1902 with the morning edition called the New York American and the evening edition remaining the New York Evening Journal.

It was also during this dynamic first decade that the newspaper cemented both its success and reputation. Hearst aimed to produce a paper that the "working man" could afford and undercut the prices of his competitors. Thus, like his earlier San Francisco Examiner, he succeeded in attracting a wide readership among both the lower and growing middle classes of society and soon outstripped the readership of the competing World and the more proletarian New York Times. Simultaneously, he began to expand the aggressive practice of sensationalistic editorializing and activist reporting that eventually made it the archetype of what would come to be referred to as "yellow journalism." The newspaper unashamedly campaigned for the instigation of what would become the Spanish-American War in 1898. In the previous year readers were treated firsthand (and in multiple installments) to "journalism that acts" as they followed the breathtaking report of Journal reporters and other Americans helping to break a young rebel, Evangelina Cisneros, out of a Cuban jail. Also, the newspaper's editors were unsparing in their harsh criticism of Republican president William McKinley until he was assassinated in 1901.

Significantly, the Journal was among the earliest American newspapers to give published credit to its reporters, columnists, editorial writers, cartoonists, and photographers. The newspaper was consistent in its pride for the individual achievements of its staff members and from this first decade onwards took up the professional practice of granting credit lines to much of its published imagery by its staff photographers and artists.

It is important to note that, in addition to subscribing to various other news services, the Hearst Corporation would also establish a successful news and picture syndication service of its own. Growing out of his rivalry with competing publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Hearst's New York Morning Journal was denied membership in 1897 to America's dominant news service, the Associated Press (AP). Although the magnate quickly gained backdoor access by simply buying up another newspaper with an earlier AP membership, his pique had been raised. In typical Hearst fashion he began to eschew both the AP and rival Edward Willis Scripps's United Press (UP) by establishing his own fledgling news syndication service around 1900. Nine years later Hearst entered the contract news syndication business with the formal establishment of his International News Service (INS) that distributed news stories by both mail and wire.

More pertinent to news photography was the invention by AT&T in 1933 of a practical means of distribution of photographs by wire. Within a year Hearst's INS had launched Soundphoto, entering into direct competition with AP's Wirephoto as well as the recently founded photoservices of other news agencies. As a result the International News Service employed many local photographers—called "stringers" like their freelance journalist counterparts—for specific assignments around the world. In addition, this arrangement also worked out well for the New York City-based, Journal-American staff photographers by expanding the exposure of their own work into Soundphoto's distribution network. The INS flourished until 1958 when it was purchased by Scripps-Howard's UP and expanded under the combined name of United Press International (UPI).

All of the editorial practices and formulas established in these formative years were propagated and flourished in the newspaper throughout its continuing decades. Both the morning American and the evening Journal were commercially successful and culturally important, reflecting both the national expansion and the economic growth of early twentieth-century America. In addition to its patriotic stance, the newspaper featured strong anti-fascist and anti-socialist positions on its editorial pages and throughout its feature stories. In addition, with the constant improvements in the technology of printing and photoreproduction, the pages of the Hearst paper proved second to none in their successful graphic and photojournalistic presentations.

Even the Hearst millions, however, could not fully protect the newspapers from the harsh effects of the multiple economic depressions of the 1930s. While its chief competitor, the World, collapsed in 1931, the morning Journal held on until 1937 when it was discontinued and the staffs were conjoined into the single daily evening issue. The final newspaper gave equal prominence to both dominant names in its titling, first as The New York Journal and American and then, in 1941, settling upon its final and lasting name, The New York Journal-American.

As its world reporting expanded and its subscriptions and sales grew steadily, the Journal-American continued its pro-American and anti-communist dominance. Its nationalism remained second to none among its competitors, especially during the opening era of the Cold War and throughout the headline-grabbing Congressional Un-American Activities Committee hearings of the 1950s. While it is unfair to label these activities with the same moniker of "media bias" that flourishes throughout our contemporary electronic communications organizations, the Hearst newspaper remained consistent in its beliefs and editorial stance. Perhaps most importantly, however, throughout its remaining decades, the New York Journal-American continued to give equal balance to its local reporting and feature writing and to its strong concentration on photographic illustrations.

The finale for the newspaper came in 1966. Hearst had died early in the previous decade, and the publications empire he founded had long been incorporated and passed on to his heirs and associates. With the rise of other technologies within world culture, most especially television, reshaping the entire information gathering and dispersal media, many daily newspapers were being modified or discontinued. Without fanfare—and, most insultingly, without even informing its staff—the flagship of the Hearst publications shut down on the evening of April 28, 1966, only three years after its sister publication, the Daily Mirror, had closed its doors. As one of its veteran copy readers, Jim Kahn, would reflect on the evening that he and his fellows were put out on the street (and headed for the local bar): "Well, the Journal was the best worst paper in America—and I loved it."

When the presses closed down on that day, the building was secured and the entire Journal-American morgue of photographs, negatives and clippings were kept intact in their original order and filing cabinets.

The Staff Photographers

Although it was not the first newspaper to successfully reproduce a photograph in halftone—that honor was taken by the New York Daily Graphic in 1880—Hearst and his editors employed a number of photomechanical printing processes, first with his San Francisco Examiner and then, most innovatively, when he took over the Journal in 1895. Photo-engravings and halftones were utilized with increasing frequency, both to illustrate stories and to support editorial content. An ever-expanding number of graphic techniques, ranging from enlargements to multiple-image layouts, quickly made the pages of the Journal look like none of its competitors—a decision that was subsequently rewarded and reinforced by rising subscriptions and street sales.

Almost from the start, the editors began hiring full-time photographers for their staff and seeing that they had all the latest cameras and supplies, as well as a full in-house lab staffed with expert technicians. The Hearst papers realized the critical and complementary relationship between words and pictures and pioneered what would become the standard practice of assigning both a reporter and a photographer to a story. And, as the photographic staffs grew, so too did the need to create morgues for managing their output and to create the important position of picture editor to handle the cameramen's assignments. In the end, the rigor and efficiency of the newspaper's photographic operation became so proficient that an image could go from the photographer, through the darkroom, and finally onto the presses in a record time of less than 90 minutes.

Although no rosters of New York Journal-American photographers have appeared, we do know the names of several of the staffers thanks both to the support information contained with their prints and negatives in the morgue as well as to the paper's early innovative practice of frequently publishing credit lines with the images reproduced in its pages.

By 1952, there were 23 photographers on the Journal-American staff, together with six darkroom technicians. We know that the publisher sponsored a yearly contest, the Hearst Newspapers' Annual Photographic Prize Competition, in which these Journal-American photographers customarily received the highest accolades. We know a few of the newspaper's picture staffers, including the camera editor Seymour Spector and the studio chief Bob "Bobby" Keogh. However, to date we know only bits and pieces about these individual photographers—and that is largely anecdotal. The history of photography and mass communications has been largely preoccupied with the largest figures in their field, while the information about such day-to-day artists or photojournalists has gone unnoticed. Still, the evidence points to their having been a remarkable company of individuals. In her memoirs of her years as a Journal-American reporter, Jeanne Toomey would recall small stories about some of their number and would summarize their collective contribution thusly: "Cameramen are among my favorite people: bold, daring, really fearless, kind and often funny."

What remains clearly evident, as the photography morgue of the New York Journal-American demonstrates, is that the output of these photographers was prodigious. With millions of their images still extant, we are left with a tangibly monumental testament to their industry and artistry. In addition, the archive's richness endures, possessing the almost infinite capacity to illustrate, amplify, and enrich our study of all the facets of a critical era of human history that played out daily before their cameras. As one editor of the morgue would reflect at the time, "These pictures stand apart even from the stories that made them."

–Roy Flukinger, Senior Research Curator of Photography

|

|

|

|

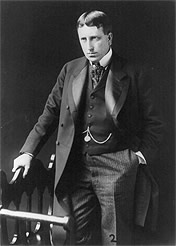

William Randolph Hearst, 1863-1951

Library of Congress Photograph

A partial listing of known photographers:

Clarence Albers

Irv Berkson

John Bermann

Matthew "Marty" Black

Brinkman

George C. Brown

Dennis Burke

Charles "Charley" Carson

Bill Cleveland

John Cosminski

Chris Daly

John DeBaise

Vic DeLucia

John Dolan

Drennan

Mel Finkelstein

William "Bill" V. Finn

Sheldon Gottesman

Bill Greenbaum (or Greenebaum)

Roland Harvey

William Hearfield

John E. Hopkins

Frank Jurkoski

Kashark

Robert "Bob" Laird

Jack Layer

Vincent Lopez

Joseph Lyons

Edward "Eddie" Mahar [later named

a City Editor for the paper]

Henry W. McAllister

James McCulla (or McCullah)

Ed "Eddie" McKevitt

Art Miller

George Miller

Leonard "Len" Morgan

Pat Mulligan

Milton B. Neuss

Jack O'Brien

David Pickoff

Ed Pickwoad

Art Pomerantz

George Reidy

Paul Rice

Frank Rino

Al Robbins

Arnold Sachs

Ben Sandhaus

Arthur Sasse

Sam Schulman

Schwartz

Weber

William "Doc" Skinner

Seymour Zee (pseudonym of

Seymour Zolatorofe)

Jerome Zerbe

|